Reconnecting through space.

“If evolutionary psychology is on solid ground, as a substantial, growing and consistent body of evidence suggests, then pleasurable responses to certain characteristics of our surrounds are built into us in ways that transcend any immediate societal trends. The rejection of such characteristics is an unnecessary frustration, their provision an obvious satisfaction of predilections that lie within us all.” —Grant Hildebrand, Origins of Architectural Pleasure (1)

Would a better understanding of our intuitive environmental preferences lead to the design of living spaces that more effectively promote psychological well-being? Spatial psychology is the study of certain spatial arrangements in architecture and landscape design and their ability to evoke somewhat predictable human responses. Some examples of work in this field include prospect-refuge and order-complexity theory. While most of what we understand about these theories to date is based on qualitative observations and experiences, quantitative research has begun to measure and better understand the specific effects and nuances of these theories.

We first became interested in this area of study years ago as a means to better understand how psychology could be applied, in the service of reconnecting people to nature, through design. In this post, we will summarize some of the previously mentioned theories and explore how we might put them to use on our project.

Elevated, sheltered outlooks like this one appeal to our evolutionary preference to observe our surroundings without being observed.

Prospect-refuge theory.

In 1975, Jay Appleton, British geographer and Academic at University of Hull, outlined the prospect-refuge theory of human aesthetics in his book, ”The Experience of Landscape”(2). His theory proposes that humans prefer spaces and landscapes where they are able to survey and gather information about what’s around them (prospect) without being seen (refuge). He argues this comes from our evolutionary-developed preference to observe our surroundings without being seen by predators. When applied to architecture, it would follow that humans instinctually prefer spaces that provide a sense of enclosure while also allowing generous views of the environment.

Examples of prospect:

• Elevated views from hill tops and structures

• A distant vista

• Unobstructed views of plains and valleys

• Large natural elements including sky, lakes and mountains

Examples of refuge:

• Shaded, shadowy areas that provide cover, like a stand of trees on a hilltop

• Caves or grottos

• Semi-enclosed or enclosed space

• Walls, screens or other physical objects to shelter behind

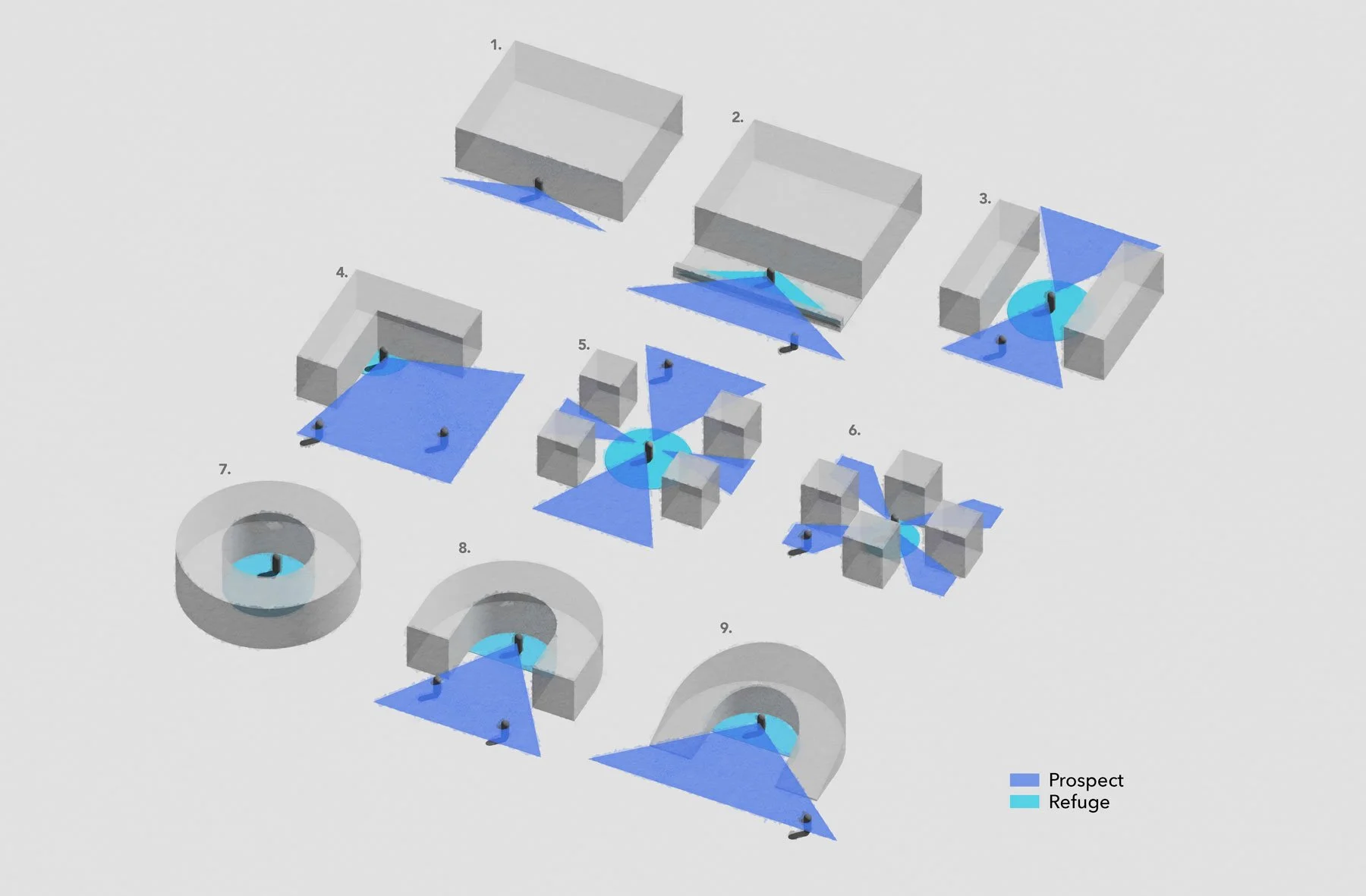

Prospect-refuge Massing Studies 1. Prospect dominant. 2. Refuge from outside viewers introduced via a terrace with hip wall. 3-6. Various spatial configurations and results. 7. Refuge dominant. 8-9. Changes in prospect resulting from altered perimeter wall massing.

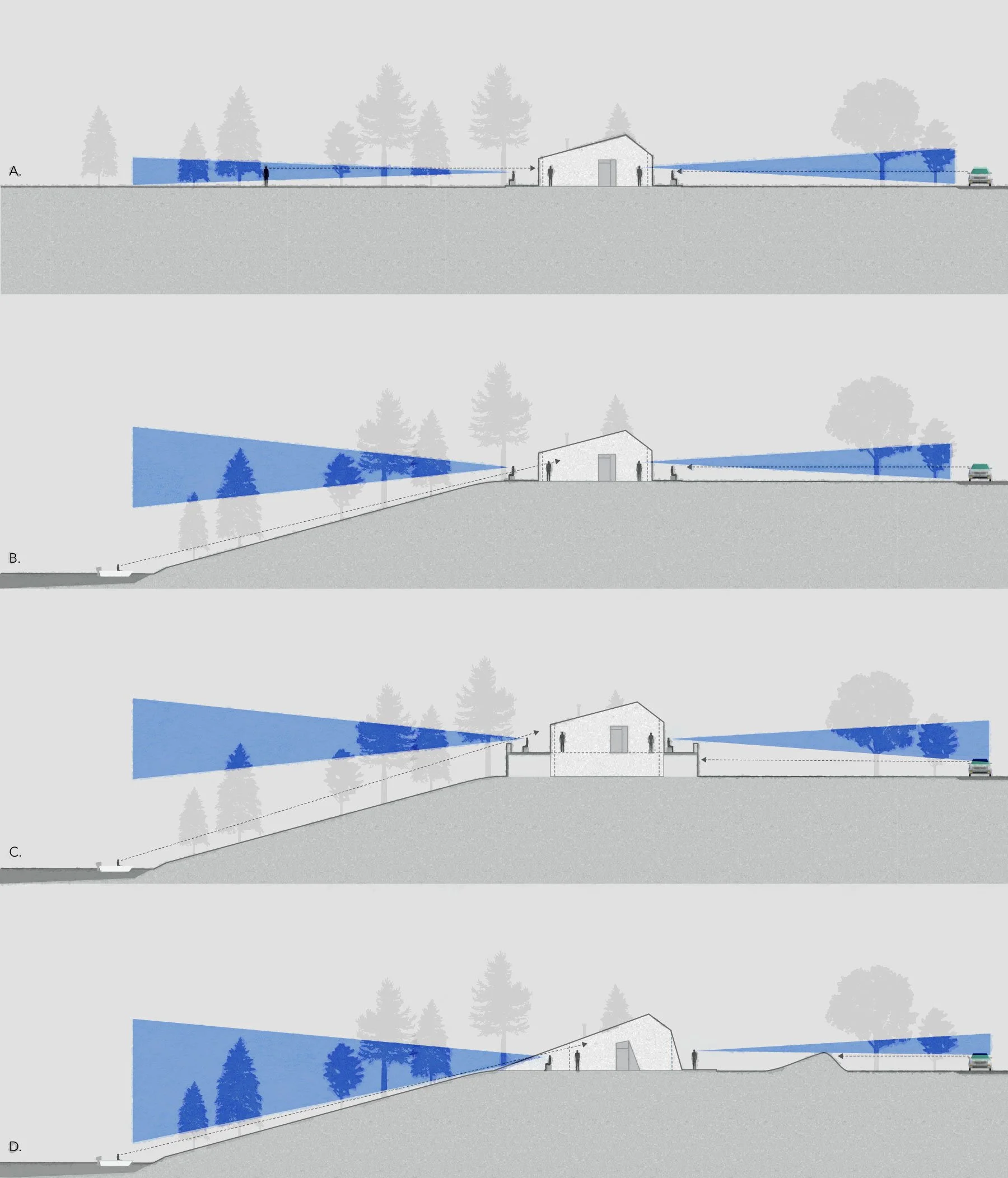

Prospect-refuge Elevation Studies A. Common level lot condition showing prospect dominant sight lines to and from the house. B. Our elevated slope condition results in increased lakeside prospect and an improved refuge condition from within the house. C. Elevated main living spaces create lake and roadside overlook advantages and screening for interior refuge. D. Grade level hybrid where siting, tapered perimeter screening walls (see 9. above), and roadside berm creates somewhat similar prospect and refuge advantages as an elevated arrangement, but from grade level. This hybrid was favored early in our design process due to its its prospect-refuge advantages, economy, sheltering look and sympathetic continuation of the lakefront slope.

In his books, “The Wright Space: Pattern and Meaning in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Houses” (3) and “Origins of Architectural Pleasure” (4), Grant Hildebrand has identified repeated spatial arrangements and patterns in Wright’s designs that show an understanding (consciously, or subconsciously) of the pleasures of space that satisfies the desire for both prospect and refuge. For instance, many of Wright's Chicago area Prairie Houses allow the their occupants to observe passing cars and pedestrians from screened or hidden positions under shadowing overhangs and behind hip-walled elevated terraces. Could his somewhat consistent fulfillment of an innate human preference be part of Wright‘s continued allure and relevance?

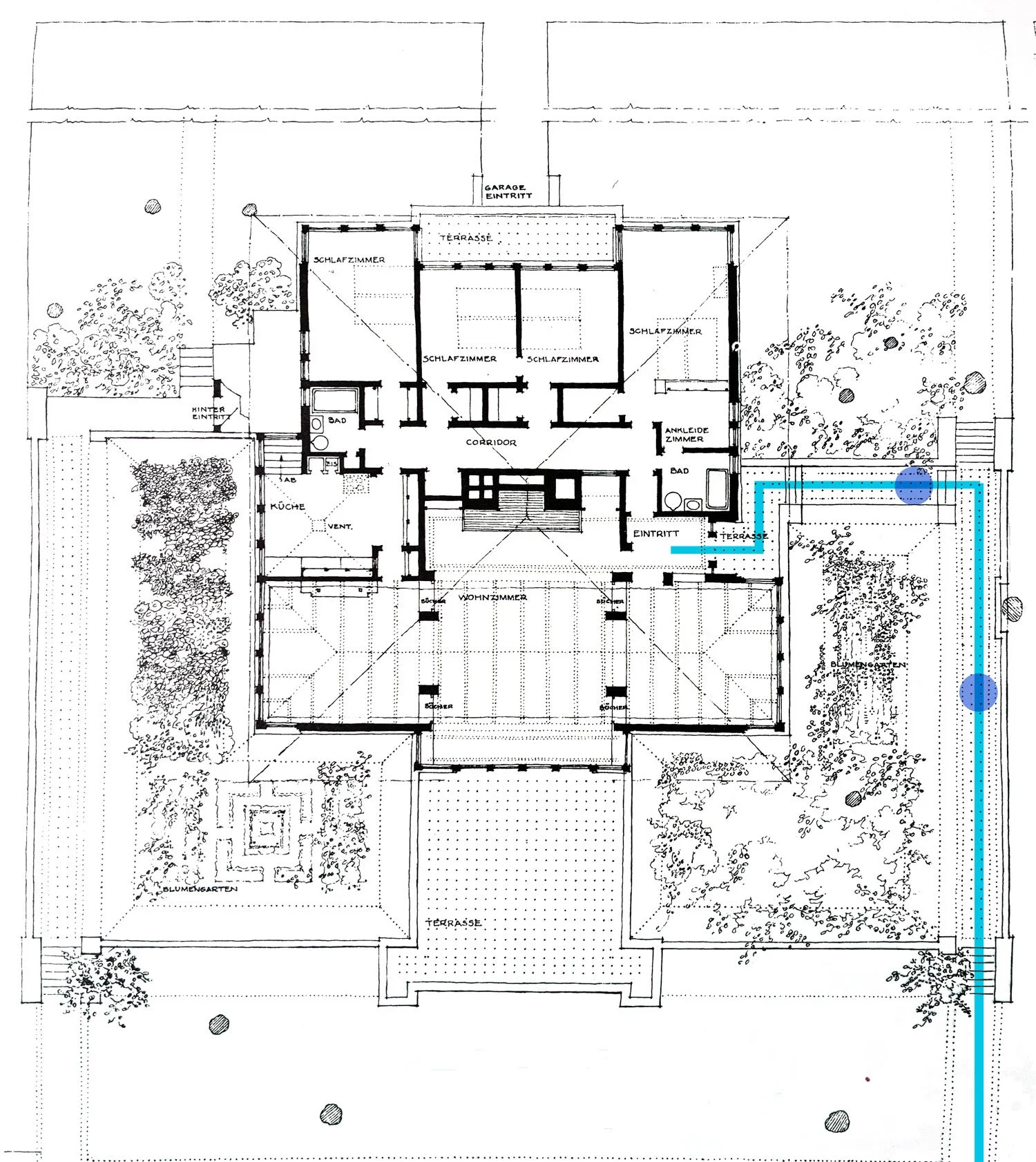

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Cheney House (1903) located in Oak Park, Illinois. This suburban home embodies many of the preferred conditions laid out in Appleton’s prospect-refuge theory. From a slightly elevated terrace, the home’s occupants are able to take in their surroundings while screened from passersby by low terrace walls, art glass windows and an interior shaded by deep overhangs. Inside, behind full-length glass terrace doors, lies the home’s living room centered around a large fireplace. Wright described this area of protective refuge around the hearth as the “heart of the home”.

Order-complexity theory.

Also known as “ordered complexity”, this second pairing of characteristics can help us understand some of our preferences when it comes to processing our surroundings. We have evolved to scan our surroundings and quickly sort information. Is that shape in the distance a rock, a group of flowers, or a threat? The more information you can take in, the more likely you will be correct in your assessment. Again, prospect is good! As we live our lives, we catalog repetitive patterns of shapes, colors, movements, behaviors, outcomes, etc. If our perception and categorization is eventually confirmed, we experience pleasure and that pattern is again reinforced. So, theoretically, we take pleasure in finding order in complex environments. It is perhaps no coincidence that more complex surroundings have historically offered more resources required for survival of humans.

We also seek out new things to analyze and try to make fit into our models of the world. For instance, you may know what a fox looks like head on, but you are more likely to be able to quickly recognize a fox if you also know what one looks like from the side. Apparently, this process of taking new information and incorporating it into our existing models also appeals to us. According to Hildebrand, we take pleasure in encountering patterns that are slight variations of the ones we already know. We are however, NOT attracted to new things that are unrelated to our past experiences. In other words, we like a good puzzle, not a chaotic, unpredictable jumble.

“The brilliance of our most recent evolutionary accretion, the verbal abilities of the left hemisphere, obscures our awareness of the functions of the intuitive right hemisphere, which in our ancestors must have been the principal means of perceiving the world.” ~ Carl Sagan

Hildebrand suggests that order-complexity theory may also be leveraged by architects and designers to create more appealing built experiences. In many ways, interior spaces can be understood as abstract versions of exterior landscapes. In Wright’s open plan prairie homes, for example, he designed landscape-like spaces complete with undulating wall, floor and ceiling planes, natural material and color palettes, bands of windows, winding circulation paths, skylights, built-in wooden screens and diagonal prospective views into adjoining spaces. All of this varied complexity was tempered by Wright through the use of ordering tools like planning grids based on window units, repeating geometric forms, themes, patterns, and a select material palette. In his book, ”The Wright Space: Pattern and Meaning in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Houses”, Hildebrand builds the case that Wright also understood the appeal of ordered complexity and set out to make his buildings a place of pleasurable intrigue, discovery and learned understanding.

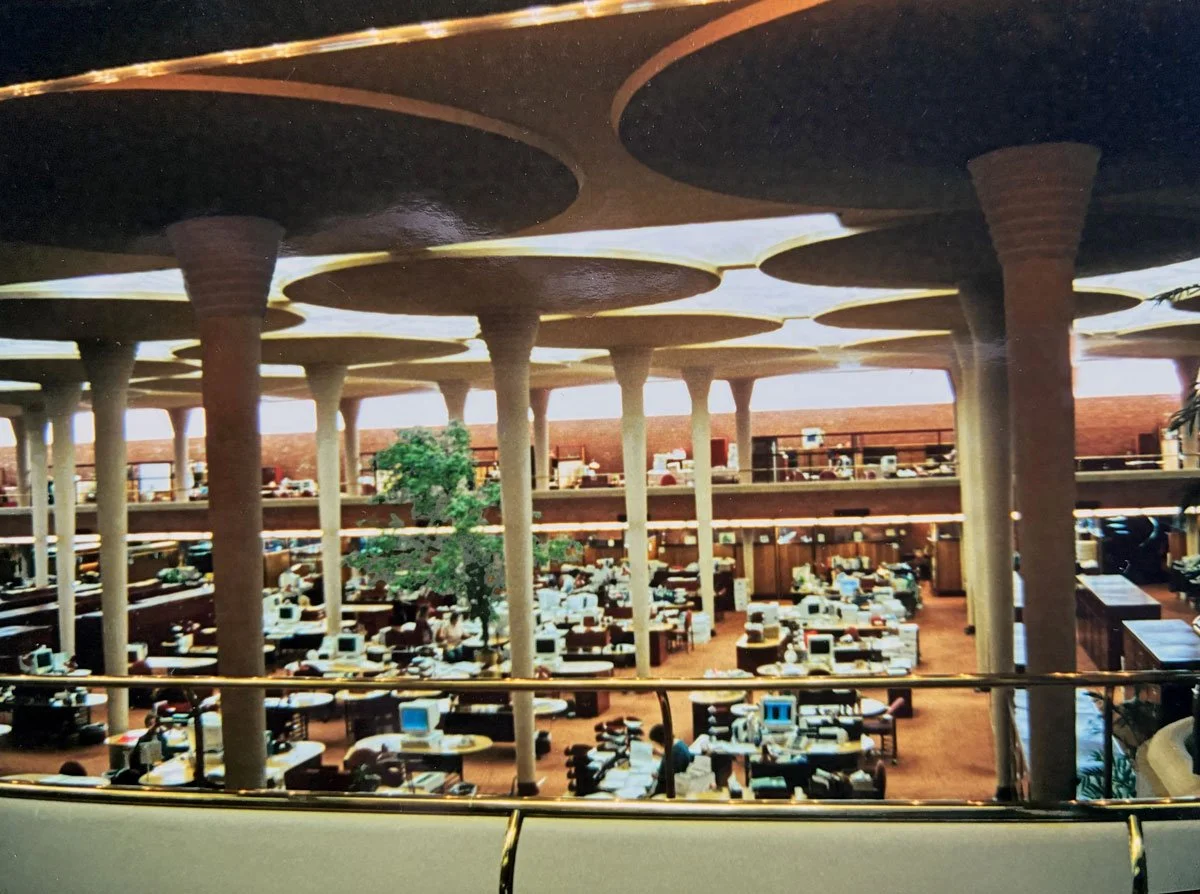

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Headquarters (1936), Racine Wisconsin. The world famous “great room” above is a dramatic example of interior prospect-refuge. The landscape-like interior, grid of the dendriform columns, skylights, limited color and material palette also appeal to our preference for ordered-complexity.

Wright’s Seth Peterson Cottage (1959), Lake Delton, Wisconsin. Living area view toward lake below is an example of interior prospect and rhythmic, ordered complexity.

Wright’s Seth Peterson Cottage (1959), Lake Delton, Wisconsin. The fireplace hearth, or “heart of the home”, is a place of snug refuge within Wright’s work. Note the lowered ceiling in this area and the use of a limited, nature-inspired material and color palette.

But what about the appeal of simplicity? Afterall, didn’t Mies van de Rohe once famously declare that, ”Less is more.”? Hildebrand puts simplicity on the side of overt order and states, “Order without complexity is monotony…”(5) He notes that while buildings like Mies’ Seagram Building in New York City (1958) prove complex in details and sections, they can appear deceptively simple to the passerby. He concludes, “There is obvious order but not enough complexity to reward attention.” Perhaps it was a lack of visible complexity in the work of many International Style architects such as Mies that led architect Robert Venturi to later quip, “Less is a bore.”

There is currently no universal formula for the perfect balance of order-complexity. Even Wright’s work veered into overcomplexity at times. For now, architects and designers should be aware that there is a human desire to see both characteristics in our built environment and do their best to design accordingly. For our project, this was a reminder to temper a favored modern, orderly planning approach with human-friendly quirks, details, patterns, textures and materials, from plan to palette.

Compression-release technique.

Based on our instinctual desire to move from dark, cramped spaces into larger, light-filled ones, the compression-release technique, sometimes called “pinch-release”, has been employed by architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright, to guide people through built space, and as a psychological trick to make rooms feel larger. For example, Wright often intentionally made his entry spaces dark and constrictive. From those dark spaces, views to light-filled adjacent living areas would entice people to move forward toward the light, prospect and freedom. An additional effect that moving from a dark, cramped space into a larger, natural-light filled one was to make the later space feel larger than it actually is through dramatic contrast.

The entry sequence of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Schwartz house (1939) in Two Rivers, WI illustrates Wright’s use of the compression-release technique in a single family home.

“We come into the world already equipped with an elaborate set of mental programs which establish probabilities as to the way we shall react in given environmental situations.” ~ Peter F. Smith

Examples of compression-release can also be found in exterior landscapes in which dark, narrow forest paths lead toward open, light-drenched clearings. Here, too, we are drawn toward the light and the possibilities that might await in the clearing ahead. Midwest landscape architect Jens Jensen utilized this design technique in the layout of the Lincoln Memorial Garden in Springfield, Illinois (1936). There, long and winding shaded forest paths are often punctuated with sun-filled clearings. One such path yields to a clearing that features a masonry council ring, a design which features a central fire hearth encircled by stone masonry seating. The council ring is said to be inspired by early human gatherings around a wood fire.

Having toured many Wright homes over the years, we can attest to the efficacy of compression-release. We plan to use this design technique in order to lead people through circulation areas, create more drama on a budget, help define zoned areas within a semi-open plan, and to make small to moderate-sized spaces feel larger.

Mystery-discovery technique.

We are naturally inclined to learn more about what is hinted at, or partially disguised, in a view. For example, walking along the path picture above, we are compelled by curiosity to keep moving forward in order to discover what is hinted at by the partially visible fence and open area beyond. University of Michigan Environmental Psychologist Stephen Kaplan has empirically validated that, ”The most preferred scenes tended to be of two kinds. They either contained a trail that disappeared around a bend or they depict a brightly lit clearing partially obscured from view by intervening foliage.”(6). He continues, ”Scenes high in mystery are characterized by continuity; there is a connection between what is seen and what is anticipated. While there is indeed the suggestion of new information, the character of that new information is implied by the available information. Not only is the degree of novelty limited in this way, but there is a sense of control, a sense that the rate of exposure to novelty is at the discretion of the viewer. A scene high in mystery is one in which one could learn more if one were to proceed farther into the scene. Thus one’s rate and direction of travel would serve to limit the rate at which new information must be dealt with. For a creature readily bored with the familiar and yet fearful of the strange, such an arrangement must be close to ideal.”

Wright is known for designing hidden front doors in his prairie houses that can only be discovered by traversing winding entry paths. The example shown below of the Cheney house entry walk contains much of the same mystery-discovery as a walk through the woods. Here, Wright weaves us into his suburban landscape and his architecture, egging us on to discover what is around the next bend, tree, brick pier or door. Wright clearly sought to play to a human preference for a limited novel experience; in this case, the eventual discovery of the front door!

The winding pathway from street to the front door of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Cheney house (1903) is an example of an architect harnessing mystery-discovery to motivate and challenge. Not only is this a pathway a journey to the front door, it also a way to prepare a visitor for the related design experience inside.

We have just scratched the surface here on the ways evolutionary preferences could be applied by architects and designers to make our homes more humane—more beneficial to our phycological well-being. It’s a shame that spatial psychology has historically played such a small part in the shaping of our built environment, beyond the work of Wright and a handful of others. However, that is beginning to change with the increased interest in the writings of Jay Appleton and Grand Hildebrand. We cannot wait to share more about how we utilized these techniques in the design of our lake home!

SOURCES:

1. Grant Hildebrand. (1999). ”Origins of Architectural Pleasure“. University of California Press. Pg. 149.2. Jay Appleton. (1978). ”The Experience of Landscape”. John Wiley & Sons. 3. Grant Hildebrand. (1991). ” The Wright Space: Pattern and Meaning in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Houses“. University of Washington Press.4. Grant Hildebrand. (1999). ”Origins of Architectural Pleasure“. University of California Press.5. Grant Hildebrand. (1999). ”Origins of Architectural Pleasure“. University of California Press. Pg. 102.6. Grant Hildebrand. (1999). ”Origins of Architectural Pleasure“. University of California Press. Pg. 52.