The primitive hut redux.

Frank Lloyd Wright said, “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.” In his quote, Wright names nature as a profound source of knowledge and inspiration while also alluding to the interconnected relationship of humans and nature.

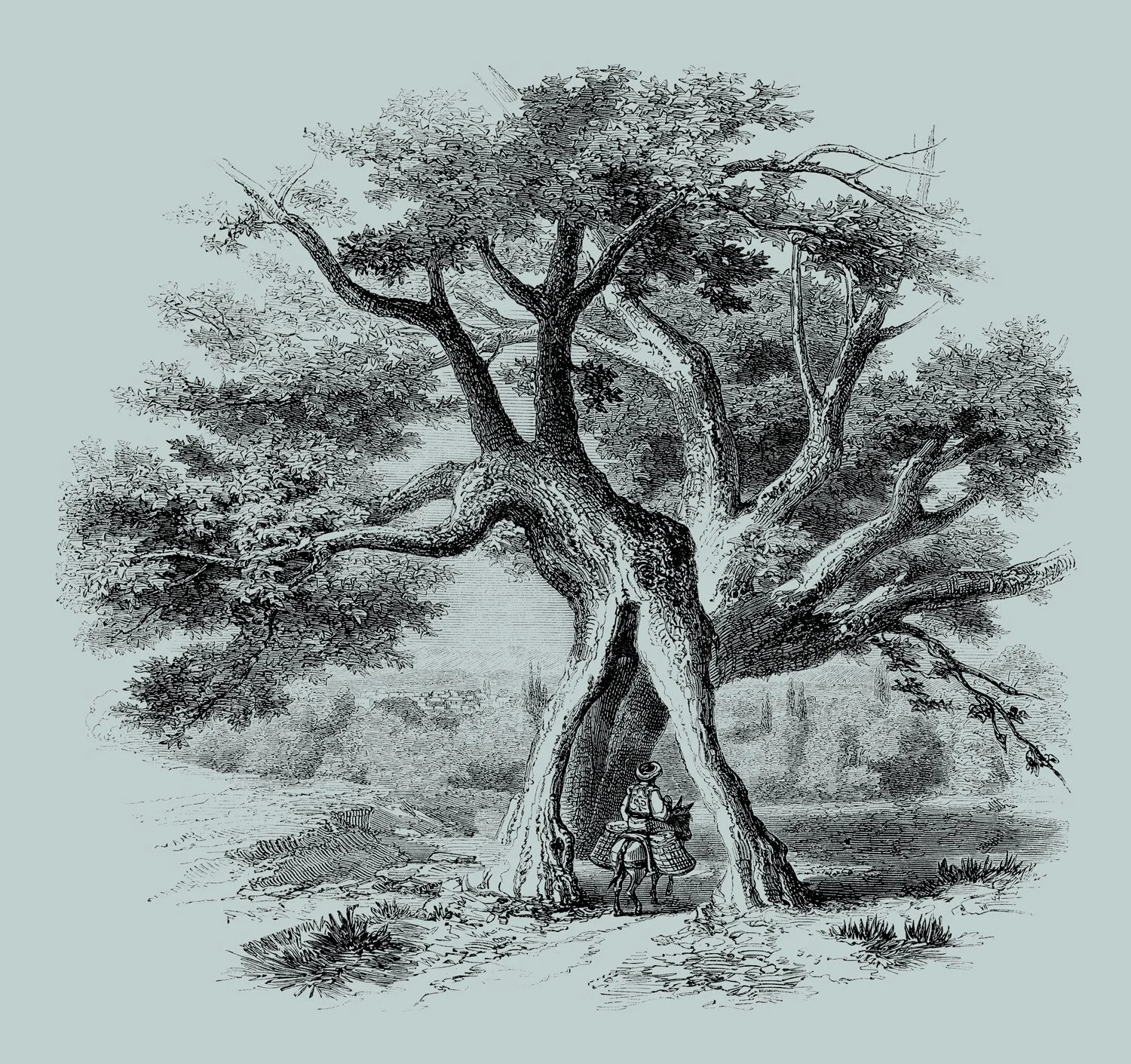

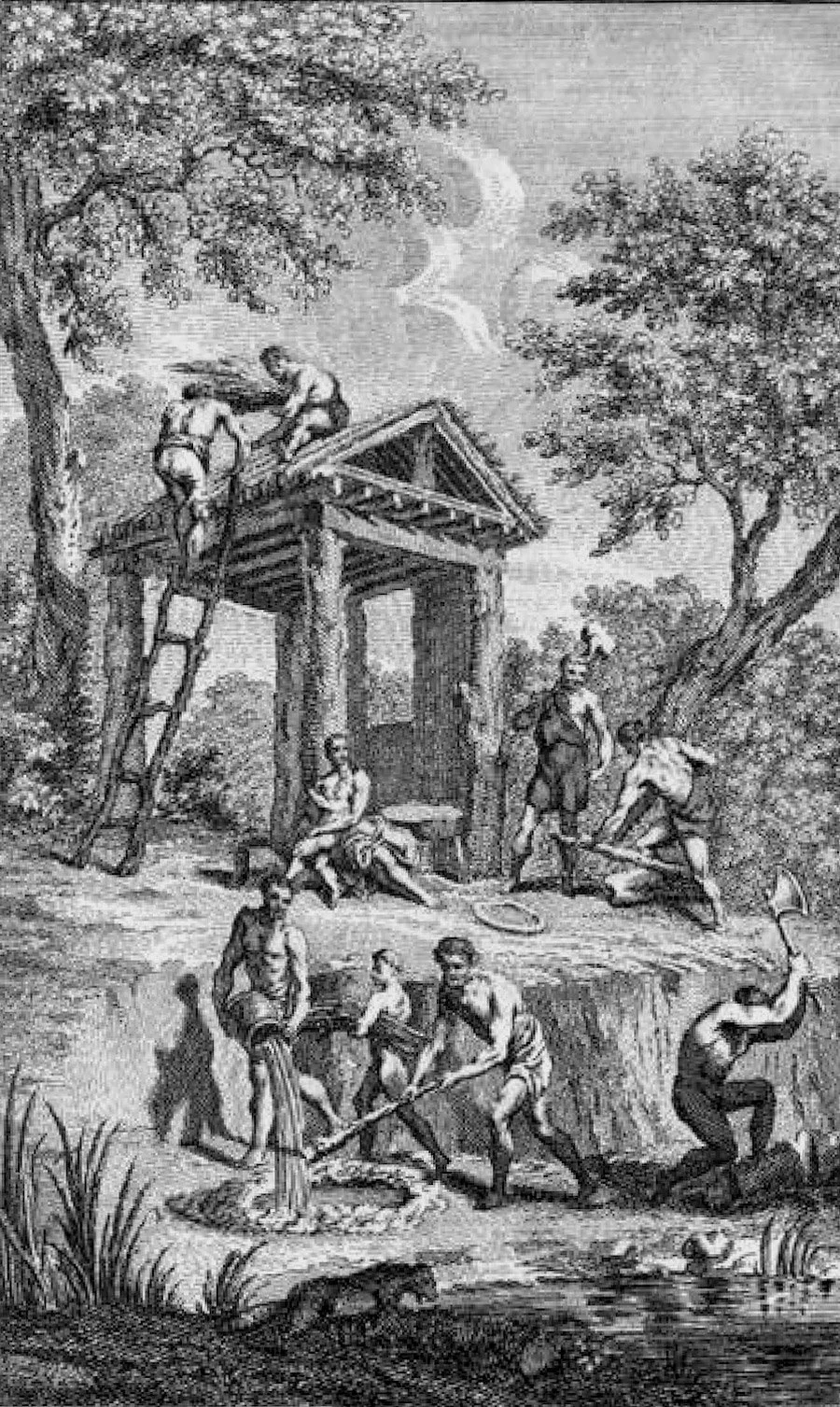

There are two famous allegorical images that depict that teacher and student relationship with nature as a possible new direction for architects. The images are frontispiece engravings dated 1753 and 1755 from The Primitive Hut (Vitruvian Hut) by Marc-Antoine Laugier(1). In the two images, we see that the trunks and branches of trees in a forest have been synthesized by early builders/architects to become the posts and beams of a primitive shelter, and the protective canopy of the trees have become roof rafters covered with plant thatching. Writing in the Age of Enlightenment, Laugier rationalized that humans first turned to nature’s example to satisfy the fundamental need for shelter. He also proposed that architecture should reject the excessive ornamentation of his own time, France’s Baroque period, and return to the underlying necessities and origins of architecture symbolized in the primitive hut. For him, “the ideal architectural form embodies what is natural and intrinsic.”(2) More on that last part in a bit.

Frontispieces of Marc-Antoine Laugier: Essai sur l'architecture. The first edition illustration suggests a new direction for architecture, ”In the image a young woman who personifies architecture draws the attention of an angelic child towards the primitive hut. Architecture is pointing to a new structural clarity found in nature, rather than the ironic ruins of the past.”(3)

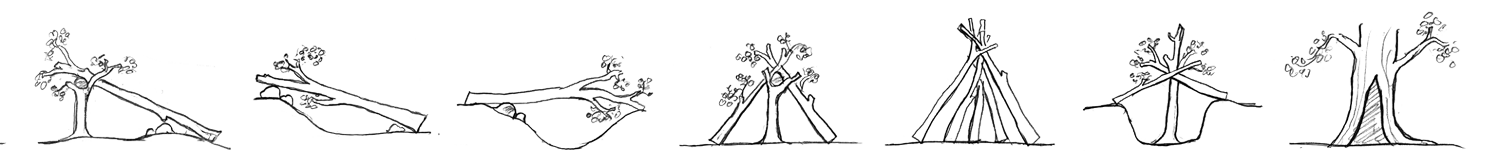

Another, less idealized example of an primitive shelter might be the common lean-to. A lean-to is made up of a a pair of tree trunks posts on one end, an overhead horizontal connecting branch beam which serves to support the top end of a set of leaned up branches. Those branches are then covered with brush and leaves to help keep the elements at bay. This type of shelter is so basic that you can see examples in nature that form randomly—when one large, leafy tree branch falls over a mound, or when one tree falls over another. The single-slope lean-to roof, or “shed roof”, remains an elegant and economic solution to roof a building to this day.

That brings me back to Laugier’s contention that ideal architectural form is both natural and intrinsic. What could he mean by that? According to architectural historians, he was calling for an architecture whose forms are derived from and harmonize with its surroundings, not historic styles. He was also suggesting that our homes once again reflect the essentials of shelter, in part by foregoing the superfluous decoration so prominent in his time.

Palace of Versailles in France (1661). The Hall of Mirrors is an example of the Baroque style and decorative excess.

It’s easy to imagine how the overwrought Baroque period and calls for a, “return to origins” could lead to reform movements. One of the most widely-known of these movements came out of early 20th century Western Europe. Born out of the German Bauhaus, the International Style famously shunned historicism and superfluous ornamentation in favor of functionalism, geometric forms and simplicity. They embraced the machine age and sleek, mass-produced materials. Celebrated works include the United Nations Headquarters, the Seagram Building, Villa Savoye, the Kaufman Desert House, and the Farnsworth House. This modern movement’s widespread influence can be seen today in everything from sleek corporate office towers and malls to minimalist contemporary homes.

Seagram Building in New York City by architect Mies van der Rohe (1958). Source: Noroton May 2008. Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs by Richard Neutra (1946). United Nations Headquarters in New York City by architects Wallace Harrison, Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier (1952).

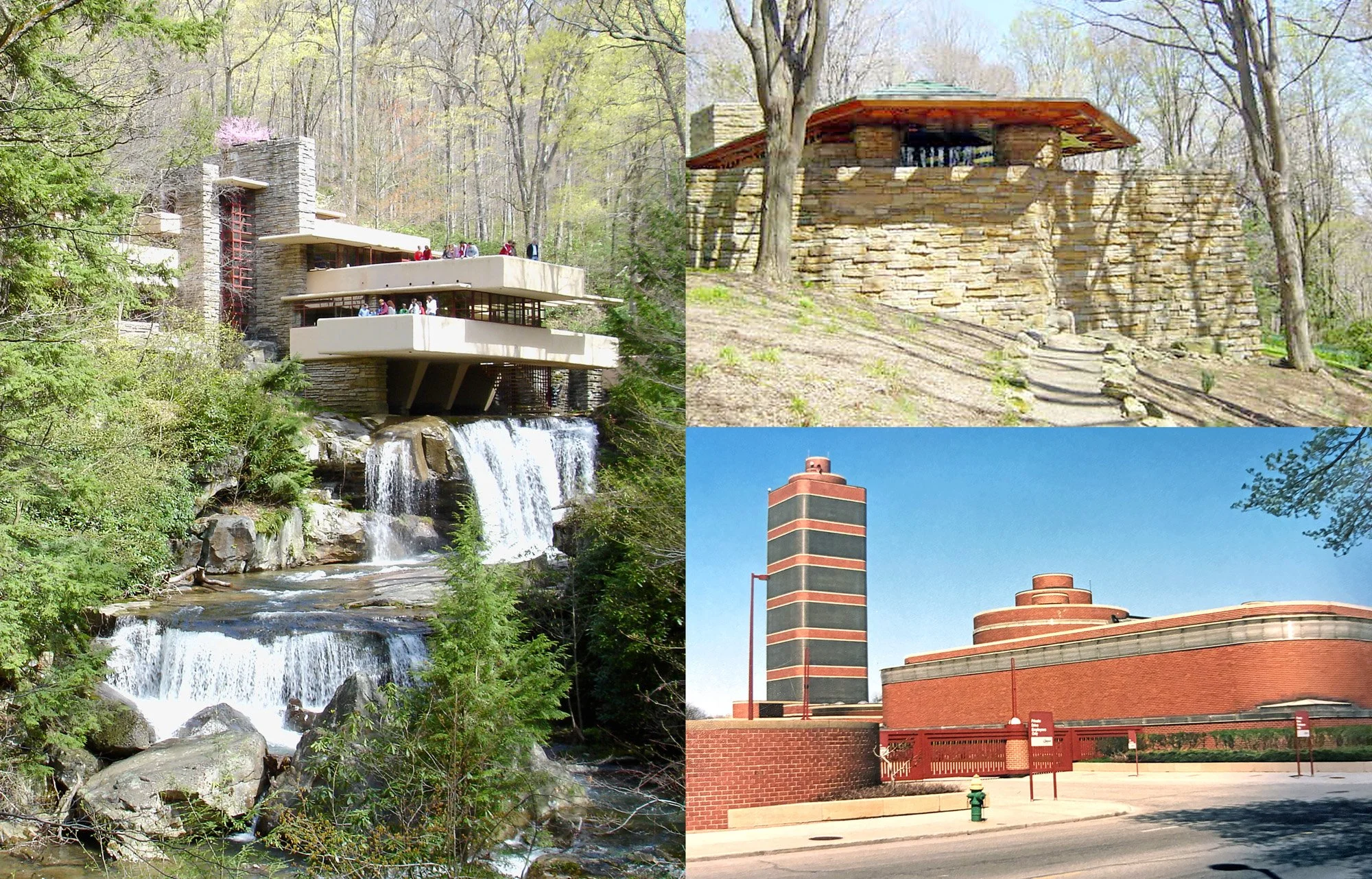

Did you know there was a second, competing branch of modern reformers that took up the cause around the same time as the Internationalists? That lesser-known branch is Organic Architecture. From its beginnings in Louis H. Sullivan’s Chicago School, and then Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School and Taliesin Fellowship, the movement of Organic Architecture sought to reform architecture using a different set of underlying principals and philosophies than the International Style. Well-known works by Organic Architects include the Johnson Wax Headquarters, Fallingwater, the Guggenheim in NYC, the Kellogg Doolittle House and Unity Temple in Chicago. The two branches of modernism were often at odds, and the differences between them relates to The Primitive Hut.

Both the International Style and Organic Architecture are thought to have sprouted from the same seed: Louis H. Sullivan’s famous saying, “Form Follows Function”. This is in part why Sullivan is sited as the “father of modernism”. But, from that identical start, the movements immediately begin to diverge. The International Style held up Form Follows Function as a call to embrace rationalism and a machine-like functionalism in the Industrial age. In his 1927 manifesto “Toward An Architecture”, Le Corbusier declared that, “A house is a machine for living in”.(4) They envisioned that their designs would be universal, easily duplicated, or even mass produced. Organic Architects, including Sullivan himself, understood Form Follows Function as a declaration that each work of architecture should develop organically to be in harmony with nature, its site, purpose, time and locally available materials. In Organic Architecture, there was no such thing as ”the style”, because each building would have its own unique style as a matter of circumstances. Wright later suggested that Sullivan's motto should be amended to, “Form and function are one”(5) to better reflect the intertwined nature of Organic Design.

A second important divergence can be found in favored forms and materials. The Internationalists favored minimalist geometric forms and flat surfaces devoid of historic or natural references. To take advantage of mass production, and to theoretically reduce labor costs, their buildings were typically constructed of modern materials like steel, concrete and glass and were often rendered in white to highlight planes and volumes. These are aesthetics inspired by the Machine Age and the trains, ships and automobiles of the time. While Organic Architects also utilized modern materials including steel, concrete and glass, they also embraced natural materials, textures and nature-inspired color palettes. They rejected the monolithic volumes and flat walls with punched out windows of the International Style in favor of undulating wall planes, ribbon bands of grouped windows, and landscape-like floor plans and spatial volumes.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in Stewart Township, Pennsylvania (1936), Kentuck Knob (top, right) in Chalkhill, Pennsylvania (1953), and Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin (1939).

Finally, I wanted to touch on the different theoretical sources of the two branches. The International Style designers set out to break the chains of historic precedents in order to create work that reflected their time and inspiration — the Machine Age. They wanted to create a universal architecture that could be mass-produced and affordable, and could be placed on almost any site. Organic Architects broke from historic architecture styles and embraced nature’s evergreen model. For them, each new project held its own unique solution, appropriate to a site, client, purpose, materials and time. So, both branches were modern in their rejection of past styles and embrace of modern materials and technologies. Yet the work of Sullivan and Wright remained connected to the past via its embrace of nature’s model — a link that reconnected modern architecture to our biological roots and the continuity of natural history.

In short, the Internationalists were inspired by the machine, and Organic Architects were inspired by nature. History has shown us that the International Style prevailed as a cultural influence. Their work was championed in the West after WWII and was widely embraced by our corporate culture for its economy, sleek aesthetic and rationalist approach. Organic Architecture, on the other hand, was said to be both blessed and cursed by its main champion, Frank Lloyd Wright. As “America’s Greatest Architect”, Wright was renowned for both his innovative work and his larger-than-life personally. Wright’s somewhat cryptic principles, tangled methods and preference that students ”learn by doing” may have limited the teachability, reach and perceived practicality of Organic Architecture. For the most part, it is thought that Organic Architecture lost momentum with Wright's death in 1959, with a few bright exceptions.

While the International Style was more influential, I feel it was the lesser branch of the two when it comes to the advancement of an ideal architecture. I would argue that the extreme mechanical rationalism of the International Style furthered the notion that humans must harness and dominate nature. It may have also bolstered idea that we were separate from nature and the past. The fault in their logic is evident in Le Corbusier’s declaration that, “A house is a machine for living in”. Their strict adherence to universal solutions, efficiency, duplication and the idealization of the machine often led to cold and inhumane solutions that could be inappropriate, or even uninhabitable. Less successful works include the Courbusier’s Unité d'habitation in Marseille, France, and any number of high-rise urban development projects of the mid 20th century.

The Primitive Hut reminds us of our historic and ongoing relationship with nature. Today’s architects and designers should continue to strive for an “ideal architecture” by once again embracing nature’s model and teachings. And, while sustainability plays a critical role in the material and energy impacts that our buildings have on the planet, we must not stop there. We must also demand and create buildings that purposely integrate with, and reconnect us to, the natural world to which we belong. We must integrate our patterns for daily living with the source of that life if we hope to have an evolved, truly rational architecture. The International Style and its machine model proved to be a tantalizing dead end. It is time, once again, to turn back to our origins.

SOURCES:

1. Frontispieces of Marc-Antoine Laugier: Essai sur l'architecture 2nd ed. 1755 by Charles Eisen (1720–1778). Allegorical engraving of the Vitruvian primitive hut.2, 3. “The Primitive Hut contends that the ideal architectural form embodies what is natural and intrinsic.”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Primitive_Hut4. “A house is a machine for living in,” rose to fame in the 1927 manifesto Vers Une Architecture (Towards An Architecture) by Le Corbusier.5. “Form and function are one”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Form_follows_function