Topography and types.

One of the things we did to help us envision our future home was to camp on the site. Luckily, there were some areas made by a previous owner for camping, as well as some trails used by the local deer population. We walked all over the lakeside slope, mapping gently sloping routes to the lake that could be managed by our older selves (we plan to retire here), as well as places for a future dock, the large trees to protect, etc. We also started to hone in on the best place for a house, and which views we wanted to incorporate.

Section of site, including zoning set back along the hillside.

Our local zoning setback falls around 25 feet before the crest of the lakeside slope. So, the topography of our site left us with a bit of latitude for how we could merge a house with the landscape. Some of the options would bring us closer to the land, while others would get us closer to the lake. Here are a few types we played with:

TYPE 1: Slab-on-grade

As the title implies, the home would sit on a ground-level concrete slab set back from the slope on the flat part of the site.

Some pros: Less excavation and foundations required; few to no steps or stairs (good for aging in place); enables us to walk directly out onto the site; possible cost savings if slab becomes finished floor surface; concrete could be used to store passive solar heat from the sun that could be released at night; and less disruption to the natural site topography.

Some cons: Pushes the house back from the minimum lakeside setback to level ground; lower floor elevation and view vantage point; larger embodied energy associated with a concrete slab; and finished floor would be harder than wood and may be cool to the touch in winter.

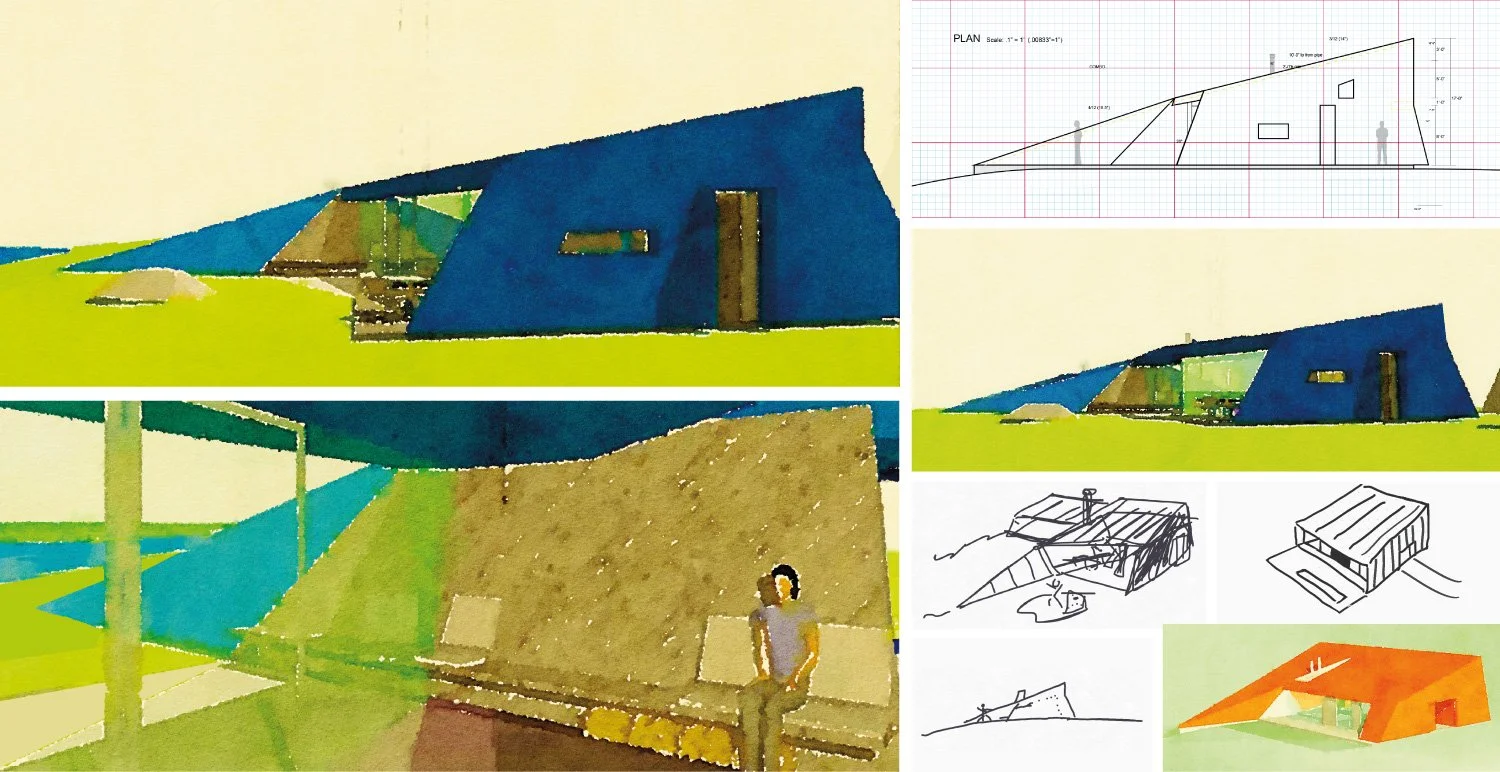

Early concepts of the slab-on-grade type. Note the sympathetic continuation of the house floor slab out to the site. Upper right elevation shows a tapered privacy wall that continues the hill line up through the roof profile. Middle right drawing depicts a pared-back version of the slab-on-grade type.

TYPE 2: Slab-on-grade with hillside terrace extension

This option is similar to the first type, but with a walk-out hillside extension consisting of a deck or terrace.

Some pros: Unlike option one, this extends the slab floor out and over the hill and could get us closer to the setback and the lake.

Some cons: Expenses associated with an added deck or masonry terrace; views inhibited by railings or walls required by code; more of a barrier between the house and the outside; and a slightly more circuitous path to reach the hill.

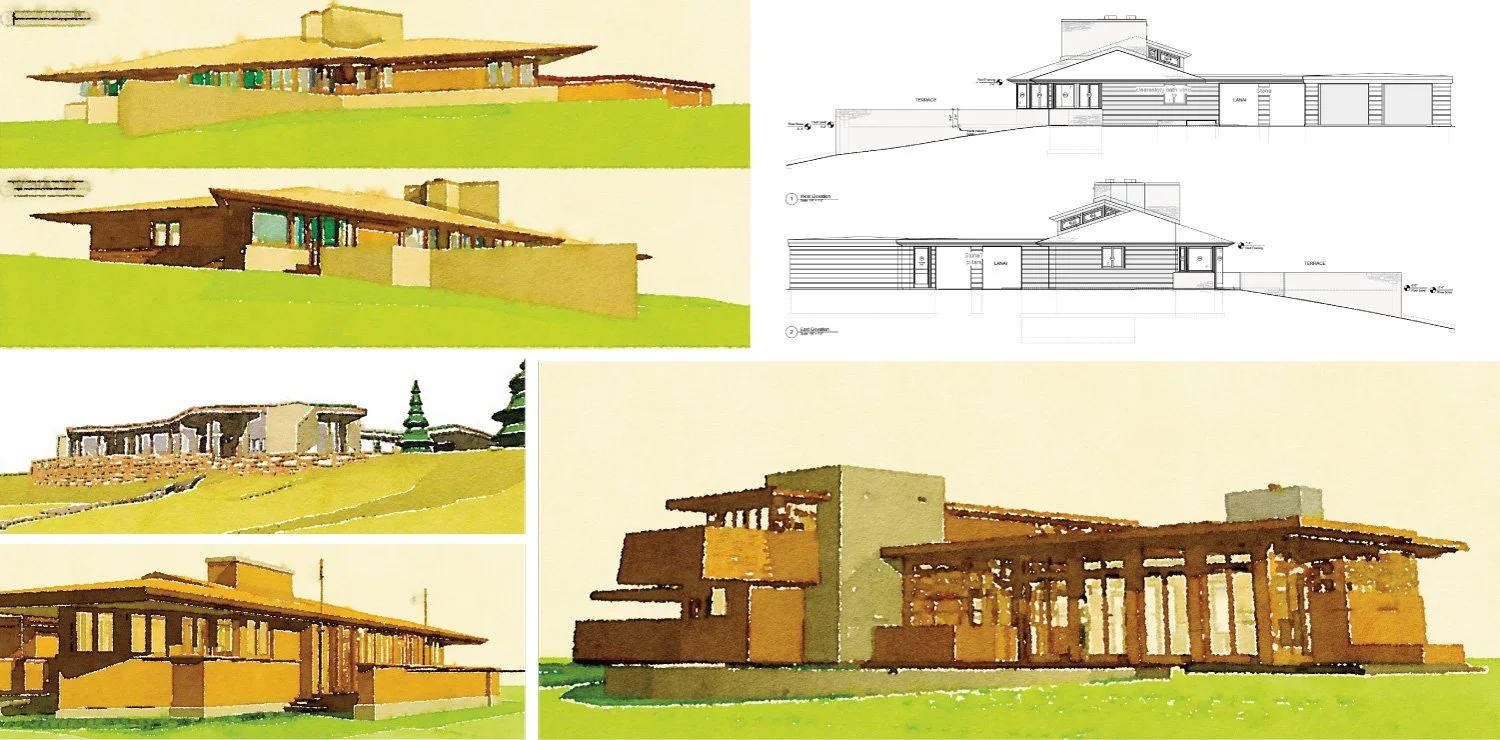

Examples of this type include Frank Lloyd Wright’s Kraus house (top), Gordon house (lower right), Wright-inspired solar hemicycle (middle left) and Prairie-style cottage (lower left).

TYPE 3: Elevated platform

This type also gets the house out over the crest of the hill using post supports, or a concrete/masonry crawlspace foundation, on the lakeside.

Some pros: Gives off slight tree house vibes; less excavation required; an elevated wood floor structure may have less environmental impacts than concrete; extends the single level floor out and over the hill and gets us closer to the setback and the lake; few to no steps or stairs; space under house could be used for kayak and other storage; and little less alterations to the natural site contours.

Some cons: Elevated platform with associated expense and required insulation; views inhibited by code required railings; lengthened path to reach the outside from the house; less capacity to store passive solar energy in a wood floor vs. concrete.

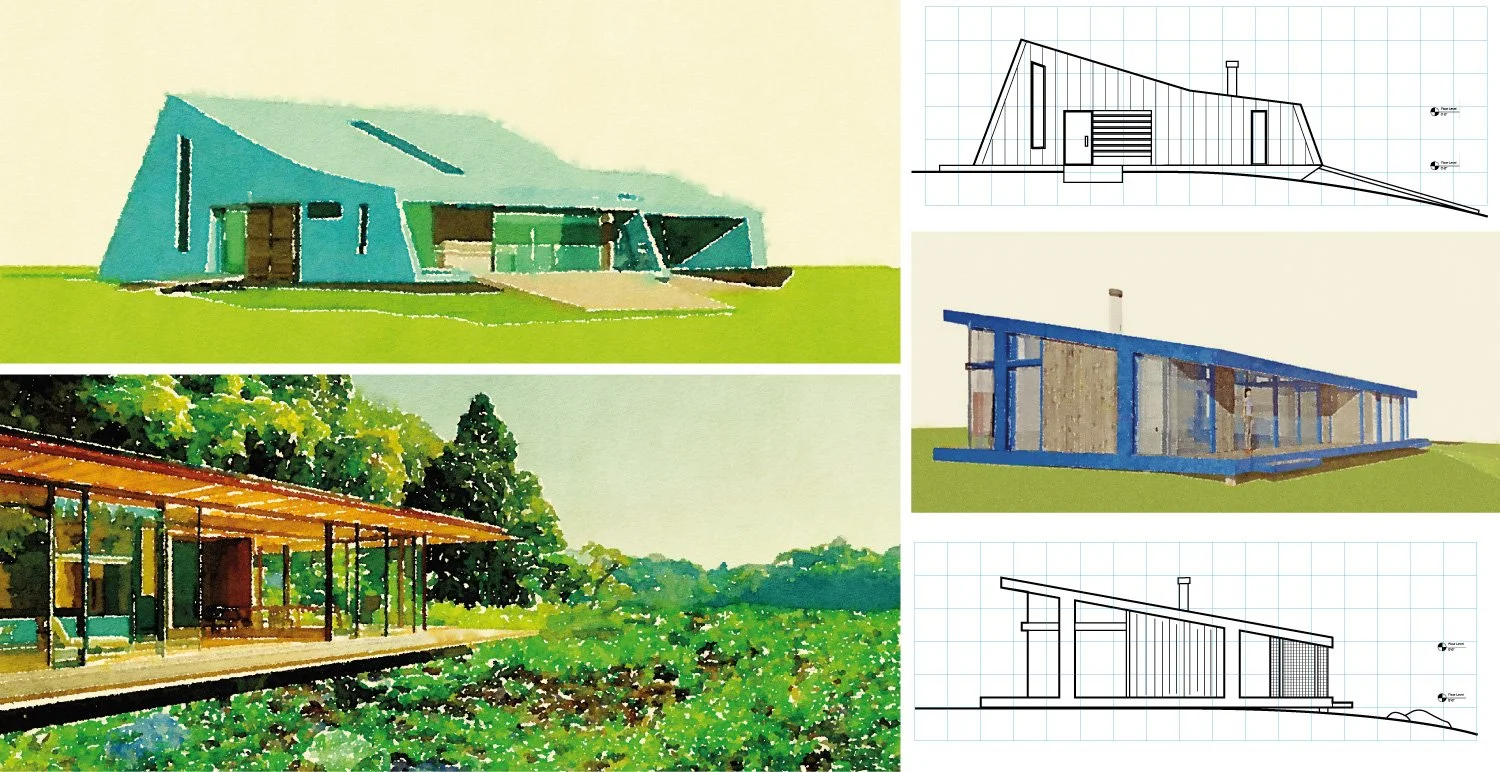

Examples of the elevated platform type. Early concepts with crawl space base and ramp deck (top row), or featuring a deck with screen porch floating on piers (middle and lower right). Lower left image is a minimalist example of this type (designer unknown).

TYPE 4: Two-story with walk-out

This building type, which features a walk-out level below the main elevated living level with connected two-story deck is popular in our area, especially on sloping sites.

Pros: Elevated sight lines; living areas or deck can be built right up to the zoning setback; increased space and convenient storage areas associated with a walk-out level; direct connection to the elevated deck from the main living area.

Cons: Excavation expense and embodied energy associated with concrete floor and concrete or block foundation walls; connection to ground inhibited by flights of stairs; added expense of a two-story structure; stairs and levels may make it harder to age in place; and views for living level inhibited by code required railings.

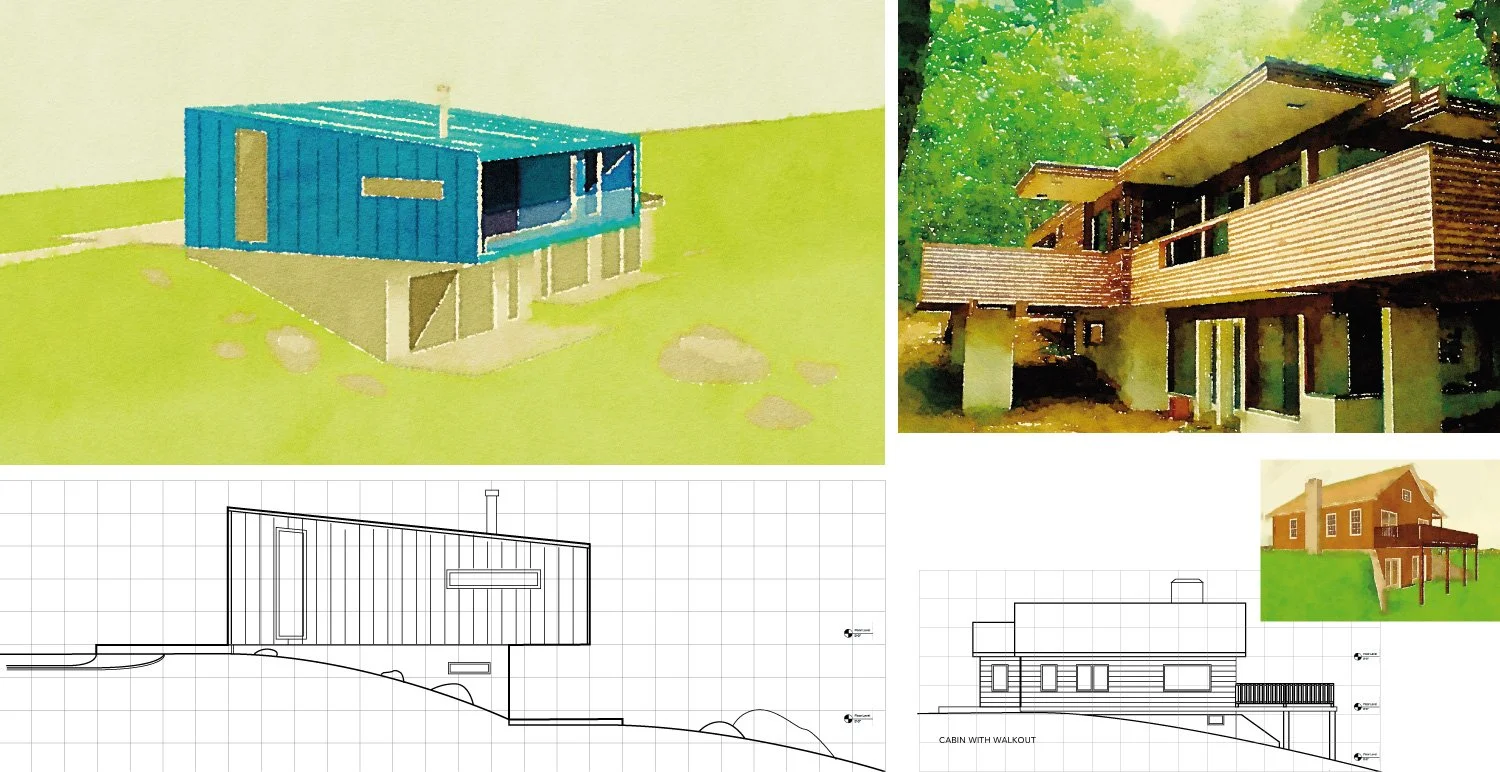

Two-story walk out concept with trendy cantilevered balcony (2 left images). The Kugel-Gips House by Charlie Zehndern (upper right) is said to have been inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. And, an example of the typical walk-out with second-story porch that is common in our area (lower right).

TYPE 5: Raised foundation with porch

Historically the most popular type of “up north” cabin. This type features a small masonry foundation (crawl space) topped with a one, one-and-one-half, or two-story living area. These homes usually feature a screened or open porch facing the lake.

Pros: Slightly elevated sight lines due to a raised foundation; can be designed with one or multiple stories; less excavation and foundation required than with a full basement; and porch over the crest of the hill gets us closer to the setback and the lake.

Cons: Expenses related to raised foundation with crawlspace; direct access to ground is somewhat inhibited by stairs off porch; traditional looking windows and doors may be less adaptable to passive solar features; raised foundation may require steps that make aging in place more difficult.

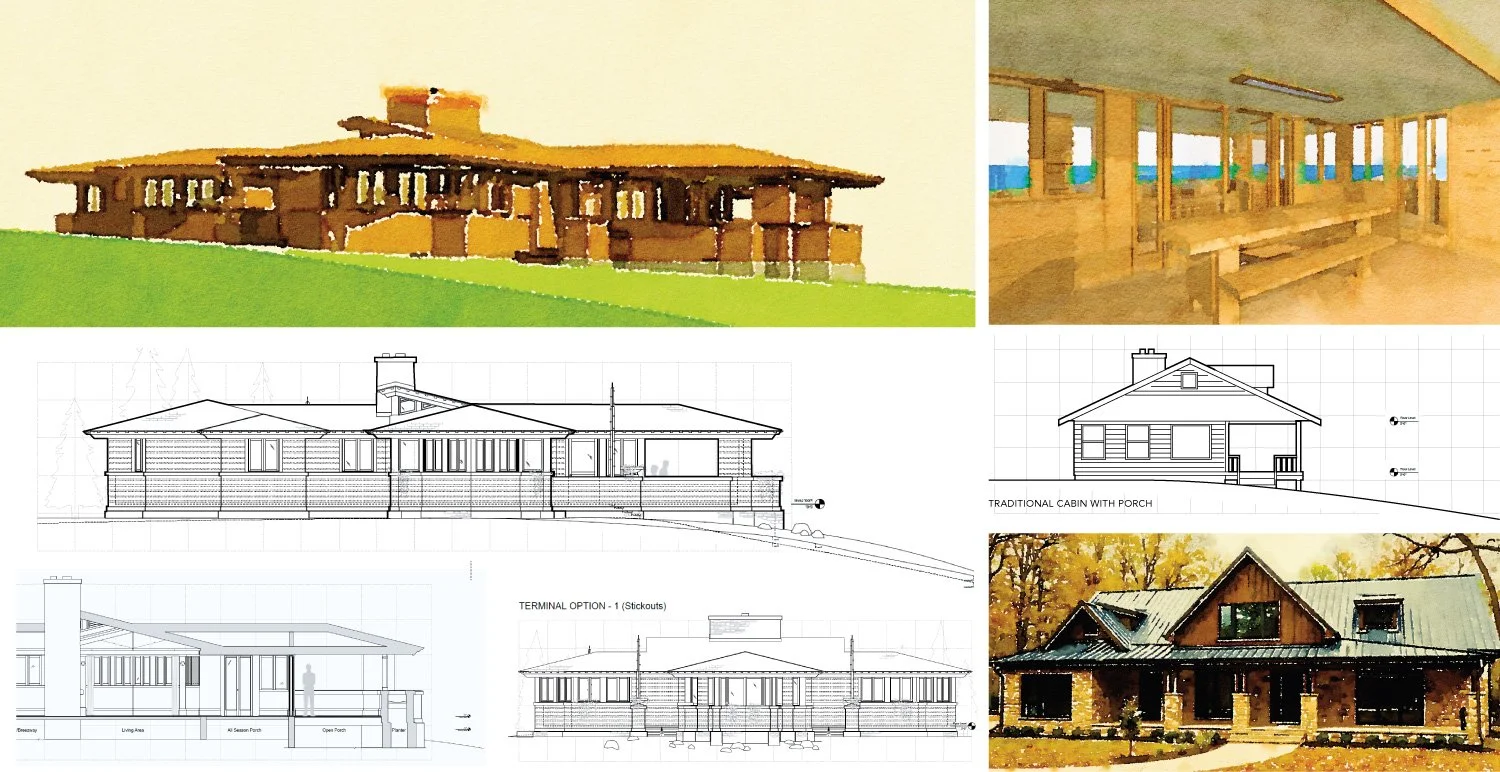

Early concepts of the porch type included a Prairie-style cottage with open porch (left column and upper right). Other examples are cabins in the Craftsman style (middle and bottom right) by unknown designers.

We spent years, well before we started construction, playing with these various building types. As you can see, we took more than a few to the CAD layout stage to better understand siting, orientation, size, program and other critical stuff. With each type, we took the time to talk over how it might effect our connection to the site/lake, our budget, sustainability strategies, etc.

If you look closely at our early concepts (identified in the captions), you can see some common features and design strategies we began to embrace.

Some of those idea are:

Each design addressed the need to capture passive solar from the south, while also taking advantage of lake views to the north, a complication that required consideration.

Several types utilize south-facing window walls and pop-up roof clearstories to capture light. Others use a pitched shed roof design to capture the light.

Each concept also takes advantage of lake views through strategic glazing and terraces or porches on the north side.

Even the larger of these early concepts reflect a human scale. There are no soaring two-story entry foyers, towering vaulted living rooms or long corridors.

The designs invite in cooling breezes from our lake to the north and a nearby lake to the south via large operable doors and windows along the north and south facades.

Most are designed (except type 4) so all rooms would be located on a single level to better accommodate aging in place.

Each design engages with the site, lake and views in different ways, including walk-out ground level patios, cantilevered terraces and elevations that reflect solar orientation and the contours of the site.

Each plan reflects a trade off of roomy bathrooms and bedroom suites for larger common areas. This was going to be an important strategy to holding down square footage and costs.

While some stretch to 2,700 square feet, most concepts fall into the 1,500 to 2,000 square foot range. Keeping the size down was always going to be critical to our ability to stay within a limited budget.